Recap: Understanding Mental Health from a Learning Perspective

By Brian Wesley Harrington, Graduate Teaching Fellow

On October 15, the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning hosted a powerful and timely workshop led by Dr. Liz Norell titled “Understanding Mental Health from a Learning Perspective.” The session explored how mental health challenges shape the learning environment and offered concrete strategies for building classrooms that support well-being.

The Landscape of Student Mental Health

Liz began with a sobering reminder: “We cannot teach brains hijacked by stress.” At any given time, one in five U.S. adults experiences a mental health condition, and local data mirror this national trend. Results from the Healthy Minds Network survey at the University of Mississippi revealed that:

- 37% of undergraduates meet the clinical definition for anxiety.

- 39% meet the clinical definition for depression.

- 12% reported suicidal ideation within the past year.

Even more striking, only 14% of students reported that mental or emotional difficulties had not negatively affected their academic performance in the previous month.

Additionally, half of respondents said they believed their peers would judge them for seeking counseling, though only 4% said they personally would judge others. As Liz emphasized, “The fear of stigma is far greater than the reality of it. The more we talk about mental health, the more we normalize it.”

Linking Mental Health and Learning

Much of the workshop focused on executive function: the set of mental processes that help us plan, focus attention, remember instructions, and juggle multiple tasks. Stress, anxiety, and depression all diminish executive function, meaning that struggling students may not lack motivation, but may lack cognitive bandwidth.

“Think about how you feel when you’re overwhelmed,” Liz said. “Tasks take longer. Concentration slips. That’s what many of our students experience daily.”

The link between fatigue and low executive functioning is particularly strong. “Decision fatigue…just figuring out what to eat for dinner can be exhausting,” she noted. “Imagine layering coursework, jobs, and financial strain on top of that.”

Isolation and the Search for Connection

Another emerging threat, Liz explained, is social isolation. Drawing on the 2023 U.S. Surgeon General’s report on loneliness, she described a nationwide “epidemic of disconnection,” exacerbated by technology.

Liz urged educators to help students cultivate genuine community: “We’re wired for connection. When students can’t find it with one another, they’ll seek it elsewhere—even from machines.” She cautioned against the growing sense of disconnection and digital isolation that technology can amplify. As students increasingly turn to AI tools for help, feedback, or even companionship, instructors are reminded of their irreplaceable role. “A chatbot can generate responses,” she noted, “but it can’t see a student, and it can’t care for them.” Her point wasn’t to vilify technology, but to reaffirm the unique value of human presence in learning.

What Faculty Can Do

After a heavy discussion, participants shifted to brainstorming small, hopeful interventions. Ideas included:

- Mindful moments at the start of class—a one-minute breathing exercise or grounding check-in.

- Walk-and-talk discussions that combine movement and conversation.

- Outdoor classes or flexible seating to reduce stress.

- Collaborative projects that build peer relationships.

- Low-stakes practice and transparency in grading and expectations.

As one participant shared, “I start each class by asking, ‘What’s one notable thing from your week?’ It changes the energy in the room. We see each other as people first.”

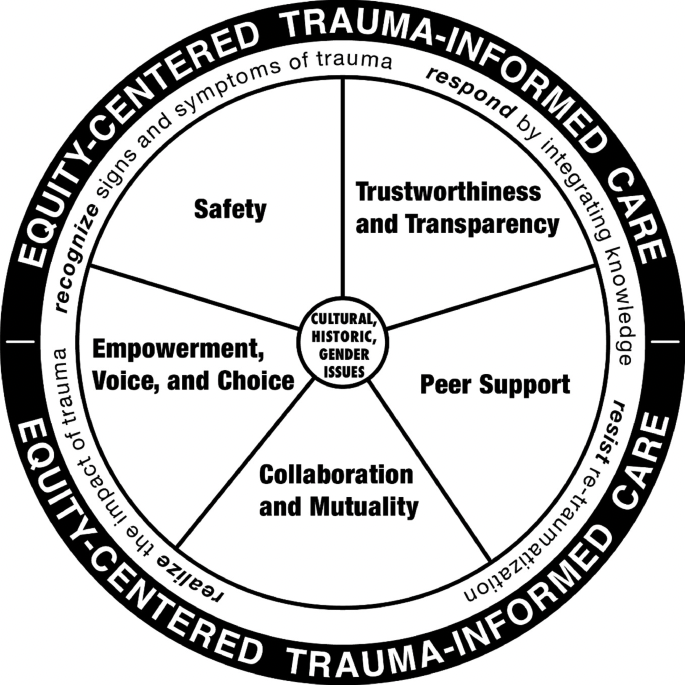

The Trauma-Informed Wheel

Dr. Norell concluded with a model adapted from trauma-informed teaching frameworks:

- Safety – Create predictable, compassionate environments.

- Trustworthiness and Transparency – Communicate expectations clearly and honor feedback.

- Peer Support – Foster connection through structured collaboration.

- Collaboration and Mutuality – Share power and decision-making.

- Empowerment, Voice, and Choice – Give students agency in their learning.

Caring as Pedagogical Practice

To care is to see students as whole people navigating pressures that extend far beyond an instructor’s assignments and deadlines. It’s about modeling empathy while maintaining boundaries, and about clarity and compassion coexisting in our teaching.

As Liz reminded attendees, genuine care is not about rescuing students or lowering expectations; it’s about creating conditions where learning feels possible. This might mean offering flexibility when life happens, acknowledging when we fall short as instructors, or simply holding space for students’ humanity alongside their academic growth.

The final message was simple but profound: care matters. “The most important thing we can do is genuinely care for our students,” Liz said. “That doesn’t mean being a pushover. It means remembering that every student in front of us is a human being with a complex life.”