Recap: When and Why Do Students Read for Class?

One possible hurdle preventing students from completing course reading assignments is the gap between the reading skills of students and those of their instructors.

On October 1, 2025, Dr. Liz Norell, Associate Director of Instructional Support at the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at the University of Mississippi, presented a workshop entitled When and Why Do Students Read for Class?, where she shared the results of her recent survey of undergraduate students and their reading habits. The workshop was designed for instructors looking to crack the code on getting their students to engage with course readings.

Liz launched the survey because she kept hearing instructors lament that “students never do the reading anymore.” But was it true that students don’t read anymore, she wondered? And was it also true that students used to do the reading? Looking at published studies, she found there wasn’t some recent golden age when students completed all or even most of the assigned reading. According to a 2000 study of 910 students by psychologists Colin M. Burchfield and John Sappington, just 20 percent of students “normally did the readings.” Other evidence supports the conclusion that reading compliance has historically been quite low.

Some research also suggests that the perceived decline in reading is not unique to university students. Liz cited evidence from a government survey about K-12 students, a Gallup Poll, and the American Time Use Survey that together showed marked declines over the past twenty years in how much and how often Americans read. “It’s not just students, it’s not just now,” Liz said. “We are all struggling with attention these days. Perhaps we’re putting anxiety on something that has always been going on.”

Reading is Hard

Liz suggested that one possible hurdle that is preventing students from completing course reading assignments is the wide gap between the reading skills of students and those of their instructors. Instructors, she explained, have forgotten what it was like to be a beginner in their disciplines, and they often overlook this gap when setting reading assignments. To illustrate this, she shared two videos from a study done by Stephen Bloch-Schulman of Elon University that illustrate the level of reading engagement by students and scholars.

In the first video, a fourth-year philosophy student reads a short text and responds aloud with one or two thoughts the text inspired. In the second video, a philosophy professor reads the same text and responds with about ten times as many thoughts and questions. The obvious difference—which drew laughter of recognition from workshop participants—was that the professor was engaging with the text in complex and sophisticated ways that were light years ahead of her student. The difference, however, was not of ability, but simply of experience. “This was a reminder,” Liz said, “that our students do not share our skills—nor should we expect them to. Our job is to help them begin overcoming that gap by modeling our own reading behaviors.” But more on that later.

What do the students say?

All University of Mississippi undergraduate students received an invitation to participate in a survey asking why and when they do the assigned reading. A total of 155 students responded, with the results suggesting that students do not think of the assigned reading as part of their homework. Ninety-six percent of respondents said they “always or almost always” complete their homework, but less than 50 percent said they “always or almost always” do the reading, even though reading was one of the tasks listed under the category of homework.

There was also a noticeable disconnect between students’ motivation, engagement, and perceived support for reading. Fifty-five percent of students reported a high motivation to complete their assignments, but less than 46 percent felt engaged with the course material, and less than 44 percent felt well supported in their efforts to learn. So the quantitative data showed that students want to learn and do what’s required for their classes, but they don’t always feel there is a strong connection between what they are asked to do and what they are actually learning.

The qualitative results from Liz’s survey found that students don’t feel the reading is useful or connected to their class performance—as in their grade. To underscore this point, Liz introduced one of her previous undergraduate students, Fisher. Fisher explained that students only read when assigned readings were obviously connected to his course grade. “If you get quizzed on [the reading] you’ll read, but with no grade given for the readings, students aren’t motivated to read,” Fisher said. The connection between grades and students’ motivation to read was supported by Liz’s survey, which found that the biggest motivator, by far, was the extrinsic one: 48 percent of students said they read because they would somehow be graded on their reading comprehension. By comparison, 31 percent of students read to be prepared for class discussion, while only 17 percent read because it was simply required.

The qualitative results revealed marked trends in why students do not do the reading.

Students don’t do the reading if:

- There are no clear incentives to read (i.e. it doesn’t feel like a good use of their time)

- They are overburdened, either by the quantity of reading or by constraints on their time, such as working

- They are not sure how to read effectively or why they are being asked to read a text.

Modest Suggestions For Assigning Reading

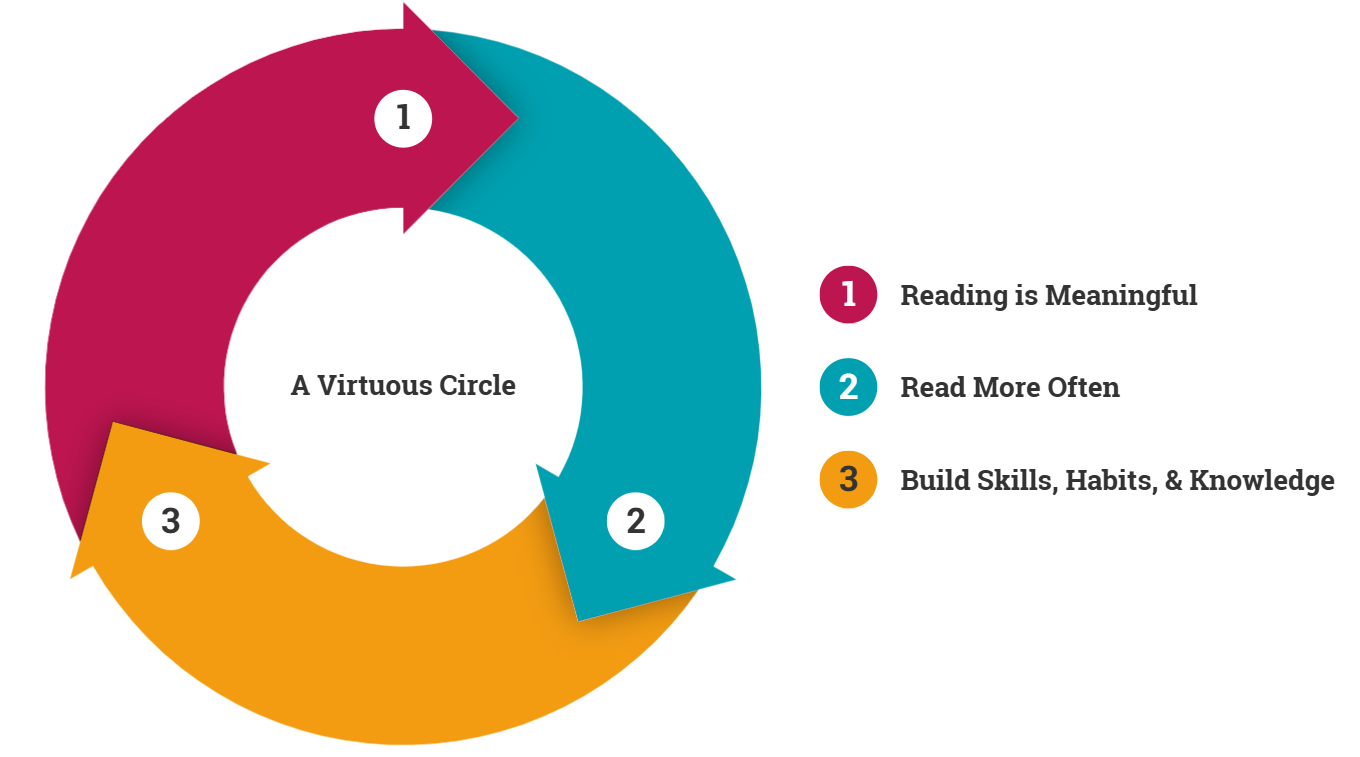

So what is to be done? Liz referenced a previous CETL workshop by Dr. Besty Barre, Assistant Provost and Executive Director of the Center for the Advancement of Teaching at Wake Forest University, that discussed how to create a virtuous cycle around reading, where meaningful reading experiences encourage students to read more often, which helps build the skills they need to read, which allows for more meaningful reading experiences. Then Liz added a few of her own modest suggestions, based on her research.

Set a good example when it comes to reading.

Model reading in front of students. Share what you’re reading. Show how you are reading and interacting with a text, and validate their struggles by talking about your own struggles with reading.

Choose your readings wisely.

Do not assume students possess the same background knowledge of the subject that you do. Remember: you’re an expert; they are novices. Be prepared to help them by supplying information to fill any knowledge gaps or deficient vocabulary.

Be transparent.

Make it clear why you assign the readings you do. Any assigned reading should have a clear and direct connection to the course objectives, and the instructor should make those connections explicit. Then provide students with a realistic amount of time to complete the reading and explain how the reading will be used (in class discussion, on a quiz, as part of some other assignment, etc.). These are all aspects of Transparency in Learning & Teaching (TILT), a framework for teaching that strives to make explicit to students the pedagogical purpose behind class assignments and activities so that they are more motivated to learn. For more about this subject, check out the recap from CETL’s recent workshop on transparent assignment design.

Activate motivation.

Show students how the reading fits in with the course objectives. Where possible, give students choices in what they read. Try to lower the stakes on the assigned reading (i.e. make it worth a low number of points) so that they don’t turn to AI to do the reading for them. And always, Liz said, consider alternative modalities for what constitutes reading. Could the assigned “reading” be an audiobook, a podcast, or something else? These are forms of reading, too.

Liz concluded by soliciting experiences from participants about how they have motivated students to do the reading in their own classrooms. One instructor commented that she makes sure to complete each week’s assigned readings alongside her students so that she never inadvertently assigns more reading than she herself can do in a busy week. Another professor explained that rather than basing her reading assignments around the texts she wanted her students to read, she redesigned her assignments around the skills she wanted them to learn (a pedagogical method known as backward design). Some of those skills might involve readings but many did not, she found.

Emily Pitts Donahoe, Associate Director of Instruction Support at CETL as well as a lecturer in Writing and Rhetoric, also shared her experiences with having students use social annotation for assigned readings. Social annotation uses online tools like Persusall, hypothes.is, or Google Docs for collaborative reading, thinking and marking up of an article or other text, and it features many of the qualities Liz recommends. It’s a great way for instructors to model how to read and to make students’ reading processes more visible to the instructor.

Liz ended the workshop with a request for instructors to encourage their students to participate in the next round of her survey, so that she can learn even more about why students do or do not do the reading. If you’d like to stay apprised of Liz’s research on reading at UM, reach out to her at eanorell@olemiss.edu.